Audience engagement is all the rage these days as the classical music field grapples with how to stay relevant in today’s culture. Many of us are asking the question of what do today’s audiences REALLY want.

Audience engagement is all the rage these days as the classical music field grapples with how to stay relevant in today’s culture. Many of us are asking the question of what do today’s audiences REALLY want.

In my class at Yale last semester, we took up this question as part of our collaborative projects. The charge to my students was to collaborate on the creation and implementation an innovative project that filled an important need for their target audience while also fulfilling the mission around which the group had rallied.

To accomplish this goal, students created their mission statements and divided themselves into 4 collaborative groups based on common missions.

Next, we utilized the creative problem solving process to identify the challenges facing classical music today, create an ideal vision of what might draw younger audiences to classical music and then come up with project ideas that had to potential to generate breakthrough solutions.

The initial project groups focused on the following problems:

- Music in Hospice

To provide access to the underserved community of families whose loved ones are dying in hospice through musical performances in the hospice facility by Yale School of Music students. - ListenUp Web App

To expand the audience for classical music for people who are curious about discovering new music by creating a web app that matches music to your mood. - Interdisciplinary Chamber Opera

To expand the audience for opera by creating and performing an interdisciplinary chamber opera in a casual cabaret setting as well as provide a behind-the-scenes look at how interdisciplinary collaborations work. - Concert of Spiritually Enriching Music

To draw in audiences of our peers by creating a concert that promotes emotional and spiritual well-being.

Creativity and innovation involve a lot of experimentation, trial and error and constant refinement and iteration. For our projects, this meant delving more deeply into the needs of the various audiences and testing out the project hypotheses to see if the projects met the needs of their audiences.

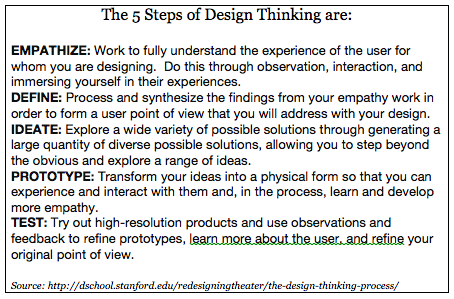

To accomplish this, we explored Design Thinking, the human-centered design process taught at Stanford’s D. School, and utilized by leading design firms like Ideo, that is based on understanding your potential users in order to design products and services that address the emotional needs of your audience.

Here is how my students used design thinking to refine their projects and come up with solutions that filled the needs of their audiences.

The four project groups focused on four different audiences:

- Music in Hospice: families and patients in hospice who need solace, as well as Yale School of Music students who wanted to do more service.

- ListenUp: peers who love listening to music and would be open to exploring other genres of music if only they would be exposed to it.

- Interdisciplinary Chamber Opera: peers who did not attend opera but who might love it in a more casual setting, as well as artists who are interested in interdisciplinary collaboration.

- Music and Wellness Concert: peers who would appreciate discovering music that could enhance their emotional and spiritual well-being.

In order to create better projects, the students needed to understand the experience that audiences had with the problem that the projects were aiming to solve.

The students thus interviewed their target audiences and showed them prototypes of their projects. This involved 3 of the 5 steps of Design Thinking.

The first step of Design Thinking is “Empathize”: to understand the experience of your audience member through observation, interaction and immersion.

Additional steps are “Prototype” where you transform your ideas into a physical manifestation of your product, and Testing where you observe and use feedback from audience members and others to refine your ideas.

Therefore, our students went out into the field to interview their audience members and show them the prototypes to find answers to the following questions:

What do your audiences need as it relates to the problem hat you are attempting to solve?

What frustrates them about this problem?

What do they want more of that you can provide?

Our students were most imaginative in conducting their interviews. Some groups interviewed audience members either in person or on the telephone, showing them sample concert programs and posters in order to gauge the audience’s reactions. Other groups created surveys which they sent out to their target users, along with their prototypes.

The ListenUP group blended the interviews and prototype testing by setting up tables on the Yale campus with a few computers and headphones (along with bagels and coffee for good measure) to find out why audiences listened to music and how they made their musical choices.

The results were quite revealing:

The Music in Hospice group had designed a serious high-minded long concert program to be performed in a specific venue. However, they discovered that their audience wanted more comfort and joy in this tender moment of their lives and that music provided this comfort. However, they were reluctant to leave their loved ones to attend a concert and would instead prefer shorter works performed at the bedside with a variety of genres including music with lyrics.

The ListenUp group gained the insight that their audience made musical choices based on their mood, not based on a specific genre of music. Therefore, the app that the group was designing needed to identify the mood of the listener and then provide music that dovetailed with that mood. Happily, there is already a mood measuring device called the Mood Meter, developed by the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence that my students began using after a class presentation by Dr. Robin Stern from the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. More on that class next time!

The Chamber Opera group found out that their audience could be expanded to families and children! Moreover, they learned that the interdisciplinary aspect of the project was not as significant to the overall success of what they were attempting to accomplish.

And the Music and Spirituality group discovered that their peers were not interested in yet another serious concert but would enjoy listening to spiritually uplifting music if it incorporated other senses, like movement through yoga and taste (through a wine-tasting event blended with a concert).

As such, the interviews and prototype testing were valuable inputs that helped to improve the projects.

How can you apply design thinking into your musical projects?

Put yourselves in the shoes of your audience members and then figure out:

What frustrates them?

What do they lack that only you can provide?

By using this method, we may very well get to the heart of what our audiences need and shape our work in such a way that we can remain true to our ideal while engaging whole new populations.

Who knows? That’s why it is vital that we experiment, iterate and keep trying until we get it right.